Patients waiting for a transplantable organ share a hope for the future that is predicated on the availability of an organ donor. Donor death must be declared prior to organ procurement. Donation after brain death (DBD) is the most common setting in which donation occurs. Organ shortages have led to donation after cardiac death (DCD). The ethical considerations related to DCD donation are challenging, yet DCD donation is increasing in response to the national organ shortage.

Considerations for Organ Transplantation

Because of the shortage of available organs not all potential recipients on the waiting list survive long enough to undergo a transplant procedure. Those who do typically wait a year or more. Prelisting assessments may be outdated by the time an organ is identified, and supplemental testing may be indicated. This testing may necessitate a deferral of the scheduled transplant, which must be weighed against the risk of further deterioration that can preclude transplantation. Untreated systemic infection, incurable malignancy, untreated substance abuse, and the lack of sufficient social support to comply with posttransplant care can preclude transplantation.

Once the decision is made to proceed with transplantation, coordination between the donor procedure and multiple recipient hospitals may be involved. Because not all donor organs are suitable for transplantation, the recipient operation should not begin until visual or biopsy-based confirmation of organ suitability has been made. During the time between the identification of the donor and the procurement surgery, the recipient’s latest laboratory values should be ascertained. If necessary, dialysis can be performed. The anesthetic plan should be reviewed with the patient and the family, questions and concerns are addressed, and the patient’s consent is obtained.

Kidney Transplantation

Kidney transplantation confers a survival advantage over dialysis for the management of renal failure. The best organ survival occurs from transplantation with grafts (kidney) from living donors, but even kidneys from marginal deceased donors confer a survival advantage over continued dialysis ( Box 36.1 ). Marginal or extended criteria donor (ECD) grafts have lower graft survival rates than standard grafts. The recently implemented kidney donor risk index (KDRI) provides a more detailed assessment of risk associated with donor kidneys than the non-ECD/ECD classification. Donor factors in the KDRI include older, hypertensive, and diabetic donors, and grafts with a prolonged duration of cold or warm ischemia, as seen with long preservation times and DCD donors, respectively.

- •

The kidney is the most frequently transplanted solid organ.

- •

More than 10,000 deceased donor and 6000 live donor kidney transplant procedures are performed annually in the United States.

- •

Five-year posttransplantation survival rates are 91% for recipients of live donor grafts, 83% for standard (non-ECD) deceased donor recipients, and 70% for recipients of grafts from ECDs.

- •

Transplantation improves survival rate over that achieved with dialysis, which carries a 20% annual mortality risk.

ECD, Extended criteria donor.

Preoperative Assessment

Because of the shortage of deceased donor grafts, the number of candidates on the waiting list continues to increase (also see Chapter 13 ). The median time on the waiting list in the United States is longer than 5 years for recipients of deceased donor grafts. This makes it challenging to maintain an up-to-date pretransplant assessment. Currently one third of kidney transplants are living-related, which facilitates scheduling preoperative evaluation and significantly shortens waiting time. Almost all living donations are performed laparoscopically; few are converted to open procedures.

Diabetes is the most common cause of end-stage renal disease, followed by hypertension, and glomerulonephritis ( Box 36.2 ). These three causes account for over two thirds of the cases of renal failure. Patients with these conditions should be medically managed to achieve treatment goals while on the waiting list.

Although cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in patients receiving dialysis, cardiovascular risk factors are often undertreated. After transplant, the cardiovascular risk diminishes from a tenfold to a twofold increase compared to that of normal patients. Accordingly, the preoperative assessment should focus on screening for ischemic heart disease and management of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Ischemic heart disease may be silent, particularly in diabetic patients. As a result of preexisting vasodilatation stress, echocardiography is probably superior to thallium imaging in predicting postoperative cardiac events, although false positive and false negative findings occur with both techniques. Coronary angiography, accompanied by therapeutic intervention for significant lesions, should be considered in patients with reversible cardiac ischemia or in those with significant risk.

Congestive heart failure is prevalent in dialysis patients but, in the absence of ischemic heart disease, does not preclude safe transplantation. Ejection fraction typically improves after transplantation. The preoperative focus is on optimal medical management of heart failure and maintenance of intravascular fluid balance.

Anemia may increase cardiovascular risk, particularly in patients with ischemic heart disease. A hemoglobin level of 12 g/dL is sufficient; higher hemoglobin concentrations may increase the risk of thrombotic events. Erythropoietin, when used to correct anemia to levels of 12 g/dL or less, lessens the risk of blood transfusion (see Chapter 24 ).

Hyperkalemia is common in patients with renal insufficiency and may be associated with increased risks during transplant surgery, particularly during reperfusion. However, mild increases in potassium may reflect normal homeostasis for renal failure, and potassium levels of 5.0 to 5.5 mEq/L are acceptable in this population. Dialysis-dependent patients may benefit from dialysis immediately prior to transplantation; however, a reduced intravascular central volume may offset the benefits of reduced potassium levels.

Intraoperative Management

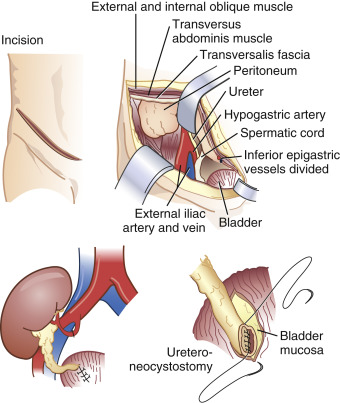

Donor kidneys are usually implanted in the iliac fossa. Vascular anastomoses are most frequently to the external iliac artery and vein, and the ureter is anastomosed directly to the bladder ( Fig. 36.1 ). Chronic renal disease can affect drug excretion via the kidney but also through changes in plasma protein binding or hepatic metabolism. When the protein binding is diminished the free fraction of the drug is increased. This results in an increase in the volume of distribution and the clearance. The net effect for the unbound fraction is similar to that in normal patients.

Some drugs require particular caution when administered in patients with renal failure. They include neuromuscular blocking (NMB) drugs (also see Chapter 11 ) and certain opioids (also see Chapter 9 ). Long-acting NMB drugs, which are excreted via the kidneys (e.g., pancuronium), are best avoided. Vecuronium and rocuronium may have a prolonged action in patients with renal failure. Cisatracurium’s duration of action is more predictable because of spontaneous breakdown (also see Chapter 11 ). Although atracurium undergoes similar elimination, it is less potent than cisatracurium, so its breakdown product, laudanosine, is found in higher concentrations. Laudanosine’s theoretical potential to cause seizures has never been clinically important.

The 6-glucuronide metabolite of morphine has clinical activity that can result in a prolonged duration of action. Meperidine should be avoided because of the seizure-inducing potential of its metabolite, normeperidine.

Inhaled anesthetics can be used in renal failure patients. Although sevoflurane’s metabolite, compound A, is nephrotoxic in rats, similar effects have not been seen in humans. Serum fluoride concentrations of 30 μmol occur in humans after sevoflurane, but do not produce renal damage. Isoflurane is metabolized to fluoride, but the extent of metabolism is so small that fluoride levels are negligible. Desflurane is not contraindicated in renal failure; but like the other volatile anesthetics, it produces a decrease in renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate in a dose-dependent manner.

Intravascular fluid balance should be maintained in patients undergoing kidney transplantation. Typically crystalloid is used for this purpose with colloids preferred by some centers. In an intensive care unit (ICU) population (also see Chapter 41 ), balanced salt solutions (e.g., lactated Ringer solution, Plasma-Lyte) are preferred over hyperchloremic crystalloids such as normal saline. These balanced salt solutions are associated with a lower incidence of acute kidney injury and a reduced need for renal replacement. Paradoxically, their effect on serum potassium levels is less than that of potassium-free hyperchloremic solutions, which are more likely to increase serum blood potassium concentrations by generating a hyperchloremic acidosis. Albumin is the typical colloid of choice; hydroxyethyl starch solution is associated with a more frequent risk of acute kidney injury.

Monitoring arterial blood pressure via an arterial catheter is avoided in some centers in order to preserve arterial access for dialysis, whereas other centers use arterial monitoring regularly in an aging recipient population with increasingly common comorbid conditions. Central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring is now recognized as a poor monitoring method of preload and fluid responsiveness. Placement of a central intravenous line should be reserved for medications that require administration into a high flow vein such as rabbit antithymocyte globulin, an immunosuppression induction drug. Induction of immunosuppression is increasingly common as efforts to increase the living donor pool include use of unrelated living donors, nondirected donors, and donor exchange programs.

Delayed graft function and acute tubular necrosis can lead to renal replacement therapy after transplantation. The factors responsible include donor hemodynamics, graft warm ischemia, and recipient hemodynamics. Adequate hydration reduces the incidence of acute tubular necrosis. There are few data to support the intraoperative use of diuretics, and there is considerable variability between surgeons regarding the intraoperative use of diuretics. Although of unproven benefit in preventing acute kidney injury in a general perioperative population, administration of osmotic diuretics, such as mannitol, during transplantation may be helpful.

Postoperative Management

Maintaining renal perfusion is an important consideration and is best accomplished by maintaining an adequate intravascular volume. Dopamine, large-dose diuretics, and osmotic diuretics are of no proven benefit in the postoperative period. Postoperative analgesia can be achieved by epidural infusion, although many health care facilities prefer intravenously administered patient-controlled analgesia with fentanyl or morphine (also see Chapter 40 ). Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs should be avoided.

Liver Transplantation

The liver is second to the kidney as the most frequently transplanted solid organ. Patients with liver failure have no alternatives to liver transplantation. The median time to transplant for waiting list candidates decreased significantly, from 14 months in 2012 to just over a month in 2013, owing to within-region sharing of liver grafts for the highest acuity recipients (those with model for end-stage liver disease [MELD] scores of 35 or more). The MELD score is used to allocate grafts based upon the recipient’s 90-day mortality risk in the absence of transplantation. International normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time, creatinine, and bilirubin are used to derive the MELD score. The most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States is hepatitis C virus, followed by alcoholic liver disease, cholestatic disease, and malignancy. Combined, these diagnoses account for 70% of candidates who are on the waiting list. New antiviral agents for hepatitis C, introduced in 2013, are expected to reduce, if not eliminate, transplants for this diagnosis in the future. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a diagnosis associated with metabolic syndrome and obesity, is expected to become an increasingly prevalent cause leading to transplantation in the coming years.

An ongoing shortage of donors has lead to the increased use of marginally viable grafts, defined as organs from elderly donors; DCD donors; donors with steatotic livers, obesity, malignancy, prolonged ICU stays, bacterial infection, or high-risk lifestyle; donors on multiple vasopressor infusions; or those who had suffered cardiac arrest.

Preoperative Assessment

Over 75% of transplant recipients are older than 50 years, compared to 63% 10 years ago (also see Chapter 13 ). A higher percentage are hospitalized and have comorbid conditions. Liver transplant candidates have many symptoms ranging from fatigue to multiple organ failure ( Box 36.3 ). Encephalopathy, common in end-stage liver disease (ESLD), can lead to sensitivity to sedative and analgesic medications, increased risk of aspiration of gastric contents, and the need for endotracheal intubation to protect the airway.

Neurologic

Encephalopathy

Cerebral edema (acute liver failure)

Cardiovascular

Hyperdynamic circulation

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

Portopulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary

Restrictive lung disease

Ventilation-perfusion mismatch

Intrapulmonary shunts

Hepatopulmonary syndrome

Gastrointestinal

Portal hypertension

Variceal bleeding

Ascites

Renal/metabolic

Hepatorenal syndrome

Acid-base abnormalities

Hematologic

Coagulopathy

Anemia

Musculoskeletal

Muscle atrophy

Full access? Get Clinical Tree